Previous Excavations

Between 1888 and 1902, a team of archaeologists led by Carl Humann (in 1888), and subsequently by Felix von Luschan and Robert Koldewey, conducted five lengthy seasons of excavation at Zincirli on behalf of the German Orient-Comité and the Berlin Museum. Their results were published in a prompt and admirably detailed manner in four large volumes entitled Ausgrabungen in Sendschirli (ed. F. von Luschan; Berlin, 1893–1911), which deal with the architecture, sculpture, and inscriptions found at the site. A fifth volume describing the most important small finds—selected pottery and hundreds of artifacts made of stone, ivory, bronze, iron, and other materials—was published some years later, in 1943, by Walter Andrae. The German excavations are described, with many archival photographs and drawings, in a book by Ralf-B. Wartke entitled Sam’al: Ein aramäischer Stadstaat des 10. bis 8. Jhs. v. Chr. und die Geschichte seiner Erforschung (Berlin, 2005).

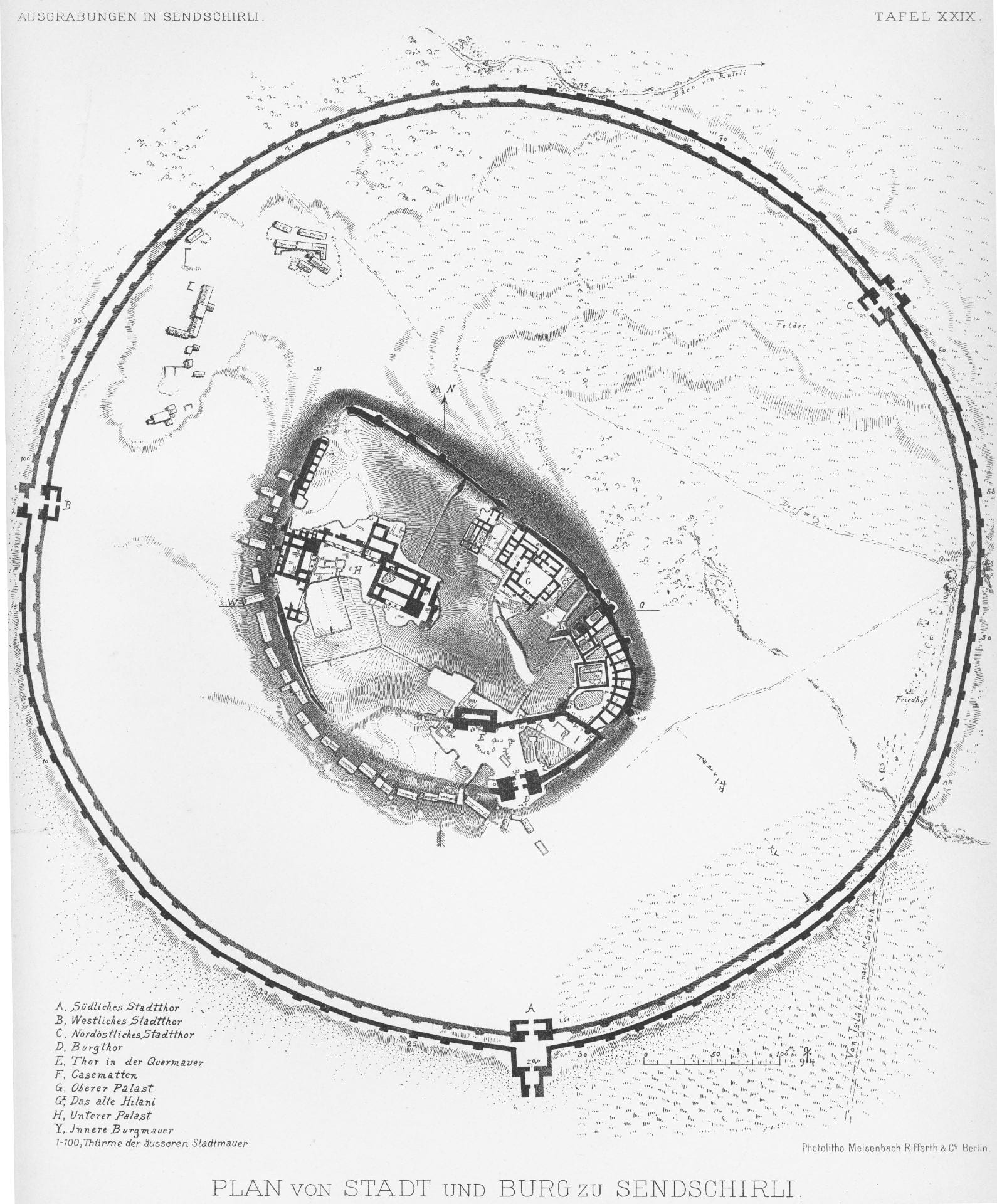

A plan made in 1894 by Robert Koldewey showing the walls and buildings of Iron Age Sam’al excavated by the German Orient-Comité expedition (from Ausgrabungen in Sendschirli, plate 29). This plan shows the three large gates and 100 towers in the double-walled outer fortifications of the city, and the citadel gate and palaces on the upper mound.

The German expedition delineated the fortification walls and gates of the Iron Age city of Sam’al. Several palaces and other large structures were exposed on the 8-hectare upper mound, which rises 15 meters above the surrounding plain in the middle of the 40-hectare site. Underneath the monumental buildings of the Iron Age were found remnants of the original Bronze Age settlements that formed the upper mound. Dozens of stone sculptures from Iron Age Sam’al were unearthed and are now in museums in Istanbul and Berlin, including statues of lions that had guarded the entrances of important buildings; decorated column bases from the porticoes of royal palaces; and rows of relief-carved basalt orthostats (rectangular standing slabs) which had lined the façades of the principal gateways into the city.

Excavations in the Citadel Gate in 1888

The German expedition also found several inscriptions, carved on stone statues or steles, which record the deeds of various kings of Sam’al. Most of these royal inscriptions were written in a local Northwest Semitic dialect called Sam’alian, thought by many scholars to be a branch of Old Aramaic. Not all of the inscriptions were written in Sam’alian, however. The earliest royal inscription we possess (ca. 830 BCE) was written in Phoenician, and the latest one (ca. 720 BCE) was written in the “official” Aramaic dialect of the Neo-Assyrian Empire. And in addition to inscriptions made by members of the local dynasty, the German expedition unearthed an imperial Assyrian inscription in Akkadian cuneiform on a large stone monument, the famous Esarhaddon Stele (670 BCE), which celebrates the conquest of Egypt in 671 BCE by Esarhaddon, ruler of the Neo-Assyrian Empire and overlord of Sam’al.

Although the methods of the German expedition were quite good by the standards of the day, and the detailed and accurate architectural plans made by Robert Koldewey are a valuable resource for modern archaeologists, the excavations were conducted rapidly on a massive scale, with only a few archaeologists managing scores of workmen. The excavators had a very limited understanding of debris-layer stratigraphy and the use of pottery to date archaeological strata. As a result, many details concerning the date and function of the buildings they unearthed are unclear, and it is difficult to associate the artifacts with their precise findspots and stratigraphic contexts. Moreover, the German expedition focused on the palaces and other monumental architecture on the upper mound, neglecting to excavate non-royal buildings in the large lower town, which constitutes 80 percent of the site.

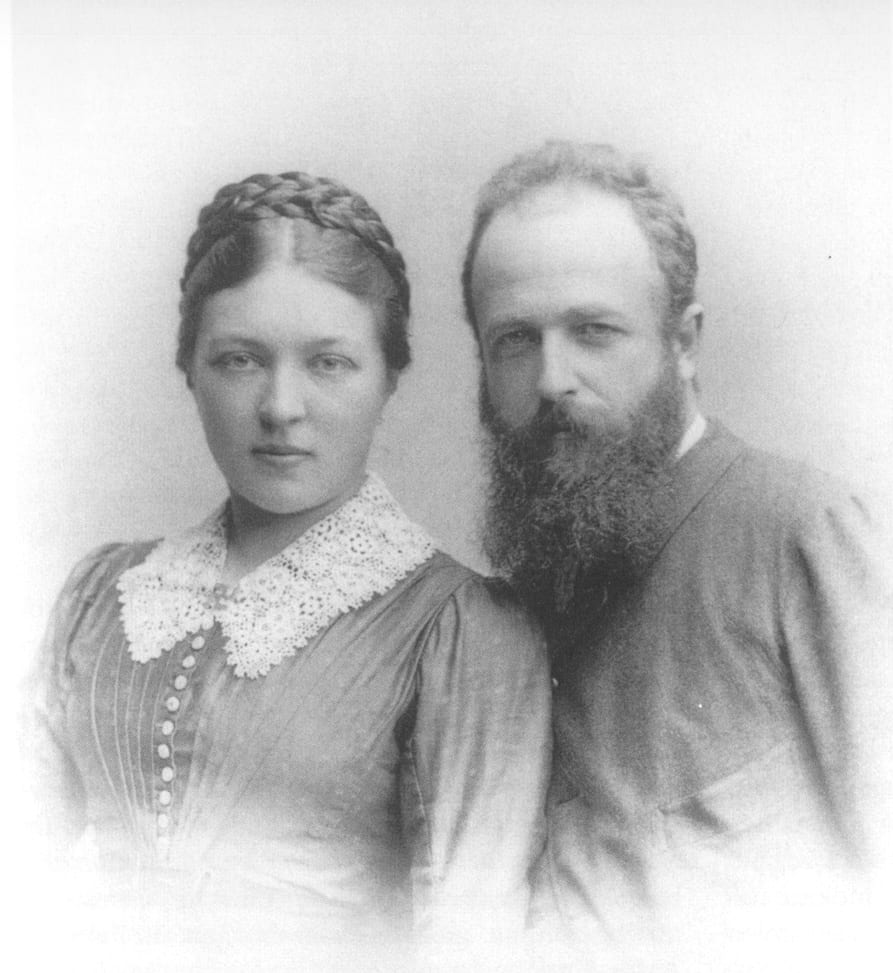

Left: Emma von Luschan and Felix von Luschan; he was the director of the German Orient-Comité excavations at Zincirli and his wife Emma served as the expedition’s registrar and photographer

Right: Robert Koldewey, the lead architectural surveyor of the German expedition to Zincirli and later the excavator of Babylon in southern Iraq